When blood drips onto another pool of blood, it doesn’t just make a mess. It leaves behind a story-one that trained forensic analysts can read like a map. These aren’t random smears. They’re physical records of movement, timing, and force. The moment a drop of blood hits an existing pool, it creates a secondary splash. That splash has shape, direction, and size. And each of those traits tells investigators something real: where the person was standing, when they moved, and even how badly they were hurt.

What Exactly Is a Drip Pattern?

A drip pattern forms when blood falls under gravity alone. No force. No impact. Just a drop, falling from a wound, a bleeding hand, or a body in motion. These are different from spatter caused by a blow or gunshot. Drip stains are slow, steady, and predictable. They’re the quiet witnesses at a crime scene.On a hard, non-porous surface like tile or laminate, a single drop creates a circular stain about 3-5 millimeters wide. But if that same drop hits a carpet? It shrinks. The fibers soak it up before it spreads. That’s why analysts always note the surface type. It changes everything.

Now imagine this: the victim was bleeding. Blood pooled on the floor. Then they shifted their weight-maybe took a step, maybe fell. Another drop fell into that pool. What happened? The drop didn’t just sit there. It exploded outward, sending tiny fragments of blood flying in all directions. Those are called satellite stains. And their pattern? It’s not random. It follows physics.

The Science Behind the Splash

In 2019, researchers at Trent University ran 500 controlled experiments using sheep blood on paper. They dropped blood from different heights-simulating different fall speeds-and recorded exactly how each drop behaved. Their findings? Two things control the outcome: velocity and number of drops.When a drop hits a pool at higher speed (say, from a height of 3 feet vs. 1 foot), the parent stain gets bigger. The satellite stains spread farther. And the shape? It becomes less round. More oval. More irregular. That’s because the force of impact overcomes the blood’s surface tension, which normally pulls it into a sphere.

Surface tension is the glue holding blood together. Viscosity-the thickness-matters too. Thicker blood, like when it’s clotting, doesn’t splatter as easily. That’s why you sometimes see stains with thick, ropey edges. That’s not just dirt. That’s blood that sat for a while before the next drop hit.

And humidity? Yes, humidity matters. In dry air, blood dries fast. In humid air? It stays wet longer. That means if two drops land seconds apart, the first might still be wet, and the second will splash. If the first has dried? The second just sits there. No splash. No satellite. That tells analysts: there was a pause.

Intersecting Patterns: The Key to Movement

Here’s where it gets powerful. When you have multiple drip patterns overlapping-when one drop hits a pool, then another drop hits the same spot minutes later-you start seeing layers. And layers mean time.Let’s say a person was stabbed in the chest. Blood drips. They stumble to the kitchen. Blood drips again. Then they collapse. Each drip location is a point on a timeline. Analysts look for convergence-the spot where all the drip paths meet. That’s the origin.

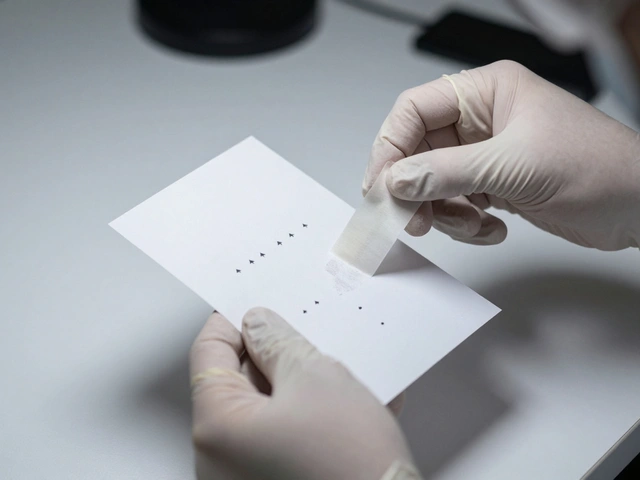

One classic method is stringing. Analysts stretch strings from the edges of each stain back toward where it came from. Where the strings cross? That’s the likely source. It’s low-tech, but it works. Another method uses geometry. Each stain is treated like the end of a triangle. The long edge points backward. The pointed end? That’s the direction the blood came from.

But here’s the catch: you can’t just look at one stain. You need intersecting patterns. One drip alone? Could be from a nosebleed. Two overlapping? Could be movement. Three or more? That’s a trail. And trails mean the person was alive and moving after being injured.

Drying Time and Sequence

Blood doesn’t dry at the same rate everywhere. A drop on a metal countertop? Dries in 30 seconds. On a wool rug? Might take 20 minutes. That’s why analysts check the edges. A fresh stain has a clean, sharp border. A dried stain? The edges curl up. The center might crack. That’s called cratering.If you see a drip stain on top of another stain, and the bottom one is cracked and dry, you know the top one came later. That’s a sequence. That’s timeline. That’s critical.

Imagine a scene: blood on the floor near a door. Another pool by the couch. A third drip trail leading to a bathroom. If the first stain is dry, the second is still slightly tacky, and the third is wet? That tells you the person bled, sat down, then got up and walked to the bathroom. They didn’t collapse right away. They had time. That changes the whole narrative.

What Drip Patterns Don’t Tell You

Drip patterns are powerful-but they’re not magic. They won’t tell you who did it. They won’t tell you the weapon. They won’t reveal a confession.They will tell you if the victim was standing, sitting, or lying down. They’ll show you if they moved after being cut. They’ll show you how long the attack lasted. They’ll help rule out accidental spills.

For example: if blood is only on the floor and the walls are clean, it’s likely the person bled where they stood. If there’s blood on the wall at shoulder height? They were likely leaning against it. If there’s a trail leading away from a pool? They moved after the injury.

And here’s something most people don’t realize: clots in the pattern matter. If you see thick, stringy blood in a drip stain, it means the blood had time to clot before falling. That suggests the wound wasn’t fresh. The bleeding was slow. The attack may have happened minutes-or even hours-before the body was found.

Tools of the Trade

Modern analysts don’t just use string and rulers. They use high-speed cameras that capture 10,000 frames per second. They use software like Fiji (ImageJ) to measure stain size, shape, and satellite distribution. They run simulations to test if a drop from 4 feet at 2.5 m/s would produce the pattern they’re seeing.Some labs now use 3D scanners to map entire crime scenes. They can rotate the bloodstains in virtual space and trace their paths backward. It’s not science fiction. It’s standard practice in major forensic labs.

But no tool replaces the analyst’s eye. No algorithm can yet tell you if a stain was made by a hand wiping blood, or if it was a drip from a wound that reopened. That takes experience. That takes training. That takes knowing what blood looks like when it’s fresh, when it’s old, when it’s mixed with saliva, or when it’s been cleaned partially-then touched again.

Why This Matters

This isn’t just about solving crimes. It’s about justice. A single misinterpreted drip pattern can lead to a wrongful arrest-or let a guilty person walk free.Think of a case: a man claims his wife fell and bled on the floor. But the drip patterns show multiple overlapping stains, all leading toward a kitchen counter. The stains show signs of movement. The wife’s injuries? Multiple stab wounds, all on her front. She didn’t fall. She was attacked. And the pattern proved it.

Or another: a teenager says he bled from a nosebleed while watching TV. But the stains form a trail from the living room to the bedroom, then back. The drying times don’t match. The satellites show velocity changes. The story doesn’t hold. The pattern does.

Forensic science doesn’t work in a vacuum. It works because people pay attention to details others ignore. A drop of blood isn’t just a stain. It’s a timestamp. A direction. A motion. A truth.

And when those drops intersect? That’s when the real story begins.

Can drip patterns prove someone was moving after being injured?

Yes. Overlapping drip stains with different drying states show timing. If one stain is dry and another is wet on top, the second drop came later. If multiple drip trails lead in different directions, the person moved between bleeding events. Satellite stains from drops hitting existing pools indicate active bleeding during movement. This is one of the most reliable indicators of post-injury mobility.

Does humidity really affect bloodstain patterns?

Absolutely. In low humidity (below 20%), blood dries quickly-sometimes in under a minute. This means drops land on a dry surface and don’t splash. In high humidity (over 60%), blood stays wet longer, so a second drop hitting the same spot will create a splash. Studies show humidity changes the shape of stains and how much they spread. Analysts must account for this when reconstructing timelines.

Are drip patterns different from spatter?

Yes. Drip patterns form from blood falling under gravity alone-no force involved. Spatter comes from high-energy events like gunshots or blunt force trauma. Drips are round, slow, and predictable. Spatter is irregular, fast, and often has fine satellite stains. Confusing them leads to major errors in reconstruction.

Can bloodstain patterns be faked?

It’s extremely difficult. Blood behaves in predictable ways based on physics-surface tension, viscosity, gravity, surface type. You can’t easily mimic the drying sequence, satellite distribution, or stain edge morphology. Even if someone tries to recreate a pattern, the subtle details-like pinning effects or micro-cracks from drying-won’t match real biological blood. Forensic labs have seen attempts, and they always fail under scrutiny.

How accurate is the stringing method?

The stringing method is reliable for basic direction and convergence, especially with 3+ stains. It’s been used since the 1970s and still holds up. But it has limits. It assumes blood traveled in straight lines, which isn’t always true. For high-velocity stains or curved trajectories, analysts combine it with computer modeling. Used correctly, it’s accurate within 10-15% of the true origin point.