When a fingerprint is matched to a suspect in court, it doesn’t mean the jury hears, "This print is 100% from the defendant." That kind of language is banned now. Instead, forensic experts must say something like, "To the exclusion of all others," or "Based on my training and the ACE-V process, I conclude this latent print originated from the defendant." The shift isn’t just about wording-it’s about how courts now view fingerprint evidence. It’s not a scientific fact. It’s an expert opinion.

How Fingerprint Evidence Got Here

Fingerprinting became a cornerstone of criminal investigations after Sir Francis Galton’s 1892 book Finger Prints laid out the science of ridge patterns. By 1911, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in People v. Jennings that fingerprints were admissible in court. For nearly a century, that was it. No one questioned whether the method was scientifically valid. Examiners said, "It’s unique. It’s infallible. It’s 100% certain." That changed in 1993, when the Supreme Court ruled in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals that judges must act as gatekeepers. They can’t just accept expert testimony because it’s been used for decades. They have to ask: Is it reliable? Is it based on sound science? Is it applied properly to the facts of this case? Since then, 32 states and federal courts adopted the Daubert standard. The rest use the older Frye standard, which focuses on whether the method is generally accepted in the field. But even in Frye states, things are changing. The 2002 case United States v. Llera Plaza was a turning point. Judge Louis Pollak initially threw out fingerprint evidence entirely. He later reversed himself-but with a strict rule: examiners can never say they’re 100% certain. Never say "zero error rate." Never say "absolute identification."The ACE-V Method: The Only Game in Town

All accredited fingerprint examiners use the ACE-V process: Analysis, Comparison, Evaluation, and Verification. This isn’t just a checklist. It’s the only standardized method recognized by the Organization of Scientific Area Committees (OSAC), which works under NIST.- Analysis: Is the latent print (the one from the crime scene) clear enough? If it’s smudged, partial, or on fabric, the examiners flag it as low quality.

- Comparison: They overlay the latent print with the suspect’s known prints. They look for matching ridge characteristics-where ridges end, split, or form islands. Most matches require at least 8-12 points of similarity, though there’s no universal minimum.

- Evaluation: This is where judgment kicks in. Is the match strong enough? Is there a plausible explanation for differences? This step is subjective, and that’s the problem.

- Verification: Another qualified examiner reviews the findings independently. If they disagree, the case is flagged for review or re-examination.

What Experts Can’t Say in Court

After Llera Plaza, courts across the country started enforcing limits. Here’s what fingerprint examiners are now prohibited from saying:- "I am 100% certain."

- "This print could only have come from one person."

- "There is zero chance of error."

- "It’s a perfect match."

- "Based on the ACE-V process, I conclude this latent print originated from the defendant to the exclusion of all others."

- "My conclusion is based on 14 ridge characteristics in agreement, with no unexplained differences."

- "The probability of a random match is not scientifically quantifiable, but the number and quality of correspondences support this identification."

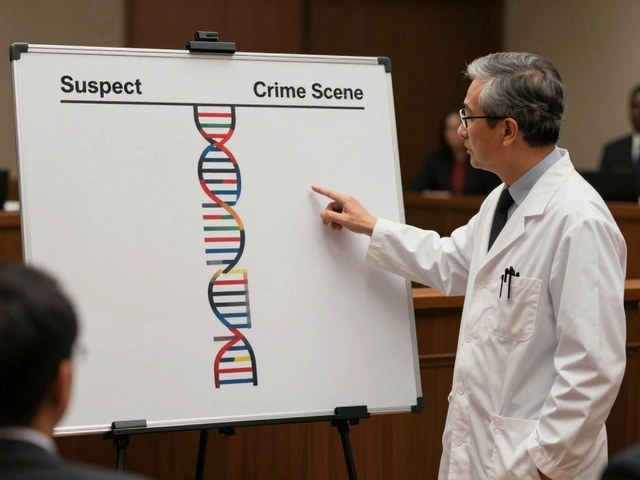

How It Compares to DNA Evidence

DNA analysis gives numbers. "The chance this DNA profile matches someone else is 1 in 1.1 billion." That’s clear. Objective. Quantifiable. Fingerprinting doesn’t have that. There’s no database of all human fingerprints. No statistical model for how often ridge patterns repeat. That’s why courts are starting to treat the two differently. In United States v. Lujan (2017), the court allowed testimony that fingerprint analysis is "more reliable than DNA" because identical twins share DNA but have different fingerprints. That’s true-but it’s misleading. DNA doesn’t claim to identify twins as the same person. It identifies the person who left the sample. Fingerprinting doesn’t have a confidence interval. It has a human examiner’s judgment. The National Academy of Sciences’ 2009 report put it bluntly: "There is a dearth of scientific research to establish the accuracy and reliability of fingerprint analysis." A decade later, we still don’t have good error rate data. The FBI’s 2011 Black Box Study found false positive rates between 0.1% and 4%, depending on experience. That’s not a small margin. It’s a legal risk.How Defense Attorneys Are Fighting Back

The 2024 National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers survey found that 78% of defense attorneys have seen more Daubert challenges to fingerprint evidence in the last five years. Judges are listening. Defense teams now routinely hire independent fingerprint experts. Costs range from $200 to $500 an hour. They review the original analysis, check for bias, and look at the quality of the latent print. One common tactic? Show that the print was partial, distorted, or taken from a porous surface-like wood or fabric-where ridge detail is easily lost. A 2021 study by Gregory Mitchell found that when defense experts challenge fingerprint testimony, conviction rates drop from 85% to 45%. Jurors aren’t buying "100% certain" anymore. They’re asking: "How do you know?" The 2022 Sakitta Project documented 18 wrongful convictions since 2000 where faulty fingerprint analysis played a role. In 12 of those cases, examiner bias was cited as the main cause. That’s not science. That’s human error.

What’s Changing Right Now

In 2023, the Forensic Science Modernization Act required all publicly funded crime labs to adopt OSAC standards by 2027. That means standardized documentation, verification protocols, and training. But right now, only 37% of municipal labs have those systems. State labs? 92% do. That’s a gap that defense attorneys are exploiting. The 2024 National Commission on Forensic Science recommended that examiners must disclose error rates in testimony. The 2025 United States v. Lujan case reinforced that: judges can allow testimony comparing fingerprint reliability to DNA-but only if the expert doesn’t overstate certainty. NIST’s 2026 roadmap says all accredited labs must start using quantitative decision metrics by 2028. That’s a big deal. It means examiners might soon have to say: "Based on our algorithm, the likelihood this match is correct is 98.3%." That’s not here yet-but it’s coming.What This Means for You

If you’re a juror: don’t assume a fingerprint match is foolproof. Ask: Was the print clear? Was it verified by a second examiner? Did the expert say "to the exclusion of all others," or did they say "100% certain"? The latter is now a red flag. If you’re a defense attorney: challenge the quality of the print. Demand the original images. Ask for the verification log. Bring in an independent expert. You’re not attacking science-you’re protecting due process. If you’re a prosecutor: prepare your examiner for tough questions. Don’t let them say "zero error rate." Train them to explain ACE-V clearly. Admit limitations upfront. The jury will respect honesty more than arrogance. If you’re an examiner: your credibility is on the line. The days of confident absolutes are over. Your job now isn’t to convince the jury you’re right. It’s to show them how you got there-and what you don’t know.Can fingerprint evidence be thrown out in court?

Yes. Under the Daubert standard, judges can exclude fingerprint testimony if they find the method isn’t reliably applied, if the examiner lacks qualifications, or if the print quality is too poor. The 2002 Llera Plaza case is the most famous example-fingerprint evidence was initially excluded entirely. Even today, 14 Daubert hearings in 2024 resulted in partial or full exclusions of fingerprint testimony.

Why can’t fingerprint examiners say "I’m 100% certain"?

Because science doesn’t work that way. No forensic method has a zero error rate. The 2009 National Academy of Sciences report and multiple studies since then have shown that human examiners make mistakes. The 2004 Madrid bombing error, where the FBI wrongly matched a print to Brandon Mayfield, proved that even top examiners can err. Courts now require experts to speak in terms of professional judgment-not absolute truth.

How often are fingerprint matches wrong?

There’s no official national error rate, but studies suggest false positives range from 0.1% to 8.2%, depending on print quality and examiner experience. The FBI’s 2011 Black Box Study found rates between 0.1% and 4%. When prints had fewer than 12 ridge characteristics, error rates jumped to 8.2%. The Sakitta Project documented 18 wrongful convictions since 2000 due to faulty fingerprint analysis.

Is fingerprint evidence still admissible in all 50 states?

Yes, but with restrictions. All 50 states still admit fingerprint evidence, but under different rules. 32 states and federal courts use the Daubert standard, which lets judges assess reliability. 18 states use Frye, which relies on general acceptance. However, even Frye states now prohibit claims of absolute certainty due to court rulings like Llera Plaza and Lujan.

What’s the difference between a latent print and an exemplar?

A latent print is an invisible or partial print left at a crime scene-usually from sweat, oil, or dirt on the skin. An exemplar is a known print taken under controlled conditions, like rolling a suspect’s fingers on ink or a digital scanner. The comparison between the two is what forms the basis of identification in court.