What You’re Really Reading When You See a Threat Letter

Most people think a threat letter is just a scary note - maybe it says, "I’ll hurt you if you don’t pay," or "You’re going to regret this." But to forensic linguists, every word, every misspelling, every comma is a clue. These aren’t just random outbursts. They’re carefully constructed messages that reveal who wrote them - their education, their emotional state, their background, even their possible next move.

Back in 1998, the FBI published a groundbreaking report that changed how law enforcement handles anonymous threats. It wasn’t just about the words. It was about how those words were put together. The report showed that even the smallest linguistic patterns - like using "you" instead of "they," or always capitalizing the first letter of every sentence - could link a threat to a known suspect. This wasn’t magic. It was science.

The Anatomy of a Threat: How Language Reveals Intent

Not all threats are created equal. A threat that says, "I’m going to make your life hell," is different from one that says, "If you don’t quit by Friday, I’ll burn down your store." The second one has structure. It has a condition. It has a deadline. That’s not accidental. Researchers call this the "bare argument structure": "If you (don’t) X, I will Y." This pattern shows the writer is thinking like someone planning an action, not just venting.

Deadlines are huge. When someone says "You have 24 hours," they’re not just being dramatic. They’re testing your response. They’re looking for fear. They want to know if you’ll comply. This kind of language shows a high level of control and calculation. It’s often tied to extortion or stalking.

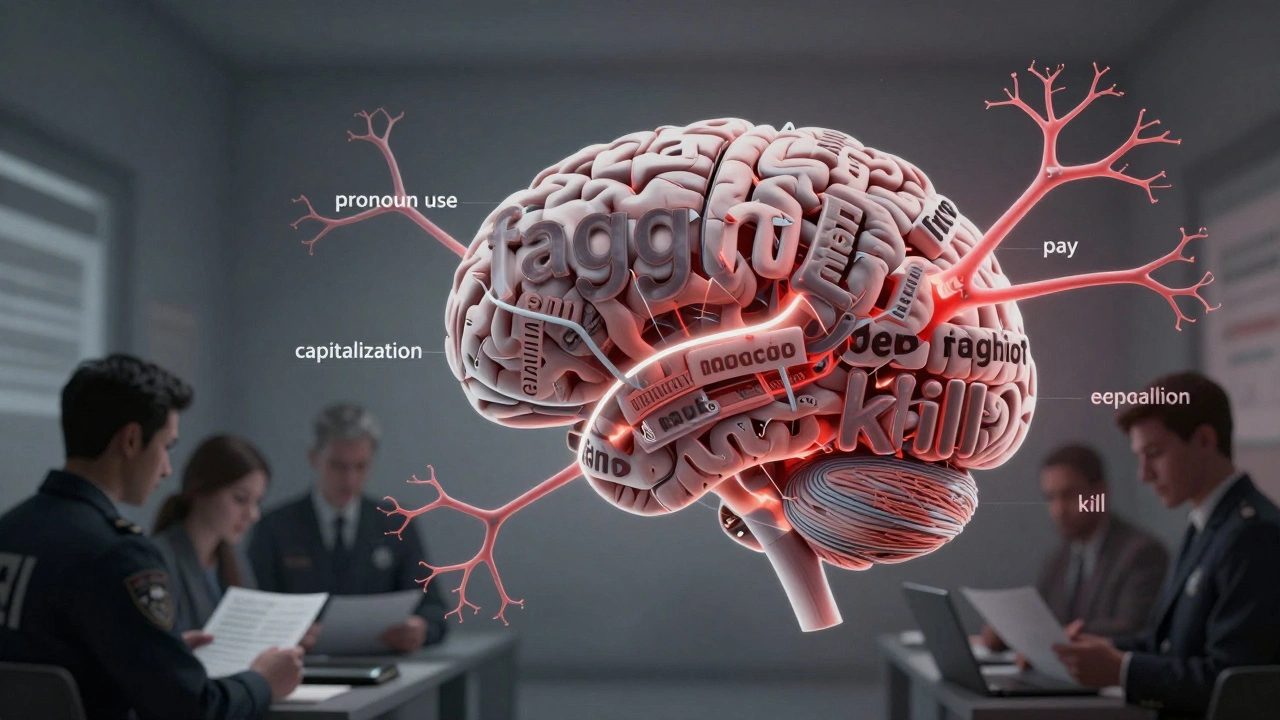

Then there’s the language of humiliation. Phrases like "Hey Faggot," "You worthless piece of trash," or "I hope your kids get sick" aren’t just insults. They’re tools. Research from 2018 showed that using negative vocatives - direct, personal attacks - increases the perceived threat by 70%. These phrases are designed to strip away the victim’s dignity before the physical threat even begins.

Handwriting, Typos, and the Silent Confession

One of the most powerful tools in psycholinguistic analysis is what’s left out. Or what’s messed up. A handwritten note full of misspellings? That’s not carelessness. It’s a fingerprint. Someone who struggles with spelling but uses complex sentence structures might have a high IQ but low formal education. Someone who writes perfectly but uses outdated slang? They might be older than they claim.

The Unabomber case is the most famous example. Ted Kaczynski’s manifesto had a very specific voice - long, academic sentences mixed with violent, emotional outbursts. He used words like "industrial society" and "technological control" but also wrote about "killing the machines." Forensic linguists matched his writing style to letters he’d sent years earlier. They didn’t need his name. They just needed his language.

Even punctuation matters. Overuse of exclamation points? Could signal emotional instability. Underlining every threat? Shows obsession. Leaving out punctuation entirely? Might indicate a lack of formal schooling - or an attempt to appear "raw" and unfiltered.

Computer Analysis: When Machines Spot What Humans Miss

Today, law enforcement doesn’t just read threats. They scan them. Software can count how often someone uses the word "you" versus "we." It can compare sentence length across dozens of documents. It can detect if someone always puts a space before a comma - a quirk most people don’t even notice.

These tools don’t replace humans. They help them. A computer might flag that a threat uses the phrase "I’ll make you pay" 12 times in three different letters. That’s not coincidence. That’s repetition. And repetition is a sign of fixation.

One study of over 300 anonymous threats found that 65% of suspects were identified using linguistic patterns alone - no fingerprints, no DNA. Just the way they wrote. The FBI now uses software that categorizes every word, punctuation mark, and formatting choice. It builds a profile: education level, possible mental health indicators, likelihood of violence.

What Makes a Threat Real? The Difference Between Bluster and Danger

Not every threatening note means someone’s going to act. Many are hoaxes. Some are cries for attention. Others are mental health crises.

Forensic linguists look for three things to judge credibility:

- Specificity - Does the threat name a time, place, or method? "I’ll hurt you" is vague. "I’ll shoot you at 3 p.m. outside your office" is concrete.

- Consistency - Does the writer use the same phrases, misspellings, or structure across multiple notes? Consistency suggests a real person, not a random prankster.

- Emotional escalation - Does the language get more intense over time? A threat that starts with "I’m upset" and ends with "I’ll kill you" shows progression - a red flag.

Researchers have identified 24 specific linguistic markers that correlate with high-risk behavior. These include using first-person pronouns when describing violence, referencing past grievances, and using religious or racial slurs to dehumanize the target. The more markers present, the higher the risk.

Who Uses This? And How Is It Done?

This isn’t just a theory. It’s used every day. The FBI’s Threat Assessment Unit, Scotland Yard’s Forensic Linguistics Unit, and INTERPOL’s Document Analysis Section all rely on it. In the UK, forensic linguists have helped solve cases involving anonymous letters to politicians, schools, and hospitals.

Dr. Roberta Bondi and Dr. John Olsson have testified in court using this method. Their analysis helped link a series of threatening letters to a single suspect in a child custody dispute. The suspect claimed he didn’t write them - but the grammar, the word choices, even the way he used capitalization matched his emails.

Academic institutions like University College London and the University of Oregon now teach forensic linguistics as part of criminal justice programs. Students learn to analyze everything from ransom notes to hate mail.

The Limits of the Method

It’s not perfect. Automated tools can misfire. A non-native English speaker might be flagged as low-education when they’re actually highly intelligent. Someone with dyslexia might be wrongly assumed to be uneducated. That’s why experts always combine computer analysis with human judgment.

One 2021 study warned that AI models trained on mainstream writing might misread non-standard dialects or marginalized speech patterns. A threat written in African American Vernacular English (AAVE) could be misclassified as "low quality" by a flawed algorithm. That’s why human linguists - trained to understand variation - remain essential.

Also, this method works best when you have multiple samples. One letter? Hard to profile. Five? Much easier. That’s why investigators collect every note, every email, every social media post from a suspect.

What Happens Next? The Future of Threat Analysis

The number of threatening communications to public figures in the U.S. rose 22% between 2016 and 2022. That trend isn’t slowing. As a result, law enforcement is investing more in psycholinguistic tools.

The latest FBI protocol, updated in 2023, now includes new markers based on hate speech patterns seen in online political threats. Researchers are testing AI models that can predict escalation - not just identify authorship, but forecast whether someone is likely to act.

The goal isn’t to catch criminals after the fact. It’s to stop them before they move from words to action. And right now, language is the best map we have.