Most people think crime happens because someone is a bad person. But what if the real question isn’t just who commits crime, but when, where, and why certain people end up in the crosshairs? Victimology doesn’t ask why criminals act - it asks why some people get targeted, again and again, while others don’t. And the answers aren’t about morality. They’re about daily habits, schedules, and environments.

Why Some People Are Targeted More Than Others

In the 1970s, criminologists stopped looking only at offenders and started studying victims. What they found was shocking: victimization isn’t random. It’s predictable. People who live in certain ways - who walk home alone at night, who work late shifts, who spend hours scrolling on public Wi-Fi - are statistically more likely to be targeted. That’s not about blame. It’s about patterns.

The Lifestyle-Exposure Theory is a framework that links personal routines directly to crime risk. Developed by Hindelang, Gottfredson, and Garofalo in 1978, it shows that your daily life shapes your exposure to criminals. Think about it: a 21-year-old male working two jobs, commuting late, hanging out in parking lots after midnight - he’s not "asking for trouble." But his routine puts him in the same places, at the same times, as offenders looking for easy targets. According to 2022 Bureau of Justice Statistics data, men aged 16-24 experience violent crime at 3.2 times the rate of women. Why? Not because they’re more aggressive. Because their routines expose them more.

Same goes for income. People in lower-income neighborhoods face property crime at rates 27% higher than those in wealthier areas. Not because they’re careless. Because homes in those areas often lack security features, street lighting, or neighborhood watch systems. It’s not about character - it’s about context.

Three Ingredients for a Crime to Happen

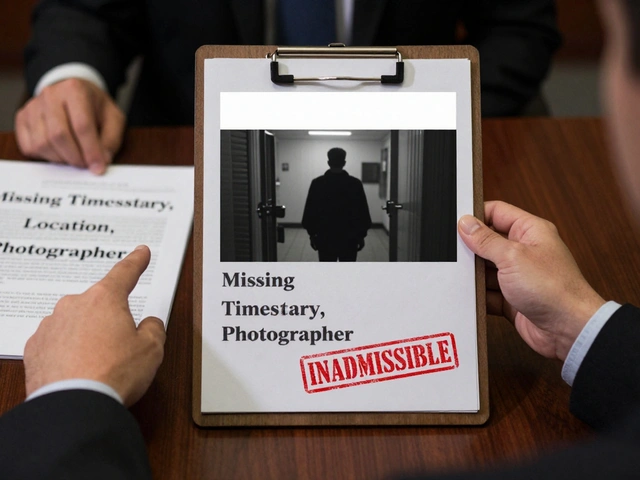

The Routine Activity Theory explains crime as the convergence of three elements: a motivated offender, a suitable target, and no capable guardian. This isn’t theory for theory’s sake. It’s used every day by police departments to prevent crime.

Let’s say you leave your laptop on a café table while you go to the restroom. You’re the target. The laptop is valuable and unguarded. If someone walks in, sees it, and decides to take it - boom. Crime happens. Now imagine that same laptop in a locked office with security cameras and an alarm. No crime. Why? Because the guardian is present.

This theory explains why most burglaries happen between 8 p.m. and 2 a.m. - when most homes are empty and no one’s watching. It explains why car thefts spike near poorly lit parking garages. It explains why pickpockets target crowded transit hubs during rush hour. The offender doesn’t need to be clever. Just opportunistic. And if the environment doesn’t stop them, they’ll act.

FBI Uniform Crime Reporting data shows 62% of violent crimes occur during those nighttime hours. That’s not coincidence. It’s calculation.

What Makes You a "Suitable Target"?

"Suitable target" doesn’t mean weak. It means accessible. Predictable. Unprotected.

Unmarried people report violent victimization at 41% higher rates than married people. Why? Not because single people are more dangerous. But because they’re more likely to be alone - walking home, using public transport, spending time in public spaces without someone else nearby. A capable guardian - a partner, a roommate, a friend - reduces risk. Not because they fight off attackers. But because their presence changes the offender’s calculus.

Same with technology. A 2025 study in the Journal of Cybersecurity found that people who spend over four hours daily on social media face 2.8 times higher risk of identity theft. Why? Because they’re broadcasting personal details - birthdays, vacation plans, work schedules - to strangers who can use them. Your digital routine is now part of your physical risk.

Where Theory Meets Real-World Prevention

These aren’t just ideas in textbooks. They’re used in real crime prevention programs.

The UK’s Secured by Design is a national program that requires new housing to include security features like lighting, fencing, and window alarms. Since 1989, residential burglary in the UK has dropped by 32%. That’s not luck. That’s design based on routine activity theory.

In the U.S., 87% of major police departments now use Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) a strategy that modifies physical spaces to reduce crime opportunities. Officers learn to spot dark alleys, broken streetlights, abandoned buildings - and fix them before crime happens.

Victim service centers use lifestyle assessments to help people reduce risk. A woman escaping domestic violence might be advised to change her commute route, avoid social media check-ins, or use a burner phone. These aren’t restrictions - they’re tools. And according to the National Center for Victims of Crime, clients who follow these routines cut repeat victimization by 44% within six months.

The Dark Side: When Theory Blames the Victim

There’s a dangerous twist. If you say "your lifestyle increases your risk," some people hear: "you brought this on yourself." That’s wrong. And it’s dangerous.

Dr. Joanne Belknap, a leading feminist criminologist, warns that applying these theories to gender-based violence risks shifting blame to women. A woman walking home alone isn’t responsible for a man who attacks her. Power, control, and systemic inequality matter more than her schedule.

That’s why modern victimology doesn’t stop at lifestyle. The Deviant Place Theory focuses on dangerous environments, not individual behavior. A neighborhood with high poverty, poor policing, and abandoned buildings is a "deviant place" - regardless of who walks there. Crime happens because the place enables it, not because the person is flawed.

And now, new research is fixing the gaps. The National Institute of Justice launched a 2024 project called "Lifestyle Risk in Marginalized Communities" - specifically to study how racism, housing discrimination, and lack of public services shape victimization. This isn’t about changing the person. It’s about changing the system.

The Future: Digital Risk and Biometric Monitoring

Today’s risks aren’t just on the street. They’re online.

Traditional routine activity theory assumed crime happened in physical space. But now, your phone location, app usage, and social media activity are part of your "routine." A 2023 update - called Routine Activity Theory 2.0 - expands the model to include digital environments. Your Instagram story showing you’re on vacation? That’s a signal to burglars. Your LinkedIn post about a new job? That’s a signal to scammers.

Even more advanced: the Department of Homeland Security is testing pilot programs that use biometric data - like heart rate patterns from smartwatches - to predict when someone is in a high-risk situation. Not to track them. To alert them. If your watch detects elevated stress while you’re walking alone in a dark area, your phone might send a safety alert: "Call a friend. Use a ride-share."

This isn’t surveillance. It’s prevention. And it’s built on the same core idea: reduce exposure, increase guardianship, remove opportunity.

What You Can Do - Without Living in Fear

You don’t need to lock yourself inside. But you do need to be aware.

- Change your routine occasionally. Don’t always leave work at 5:15 p.m. and take the same route home.

- Use privacy settings. Don’t post "on vacation" until you’re back.

- Carry a flashlight. It’s not for seeing - it’s for signaling. A lit area is less attractive to offenders.

- Know your neighborhood. Which streets feel safe? Which ones feel empty? Adjust your paths.

- Use apps like Find My Friends or Life360. A trusted person knowing your location is a digital guardian.

Victimology doesn’t tell you to be afraid. It tells you to be smart. Crime isn’t random. It’s opportunistic. And opportunity can be reduced - without giving up your life.

Is victimology about blaming victims?

No. Victimology is about understanding patterns - not assigning blame. While early theories sometimes led to victim-blaming, modern victimology focuses on environmental, social, and structural factors. The goal is prevention, not judgment. Experts like Dr. Bonnie Fisher and the American Society of Criminology stress that these frameworks only work when they respect victim agency and address systemic inequalities.

How accurate are lifestyle and routine activity theories?

They’re among the most accurate in criminology. Studies show lifestyle factors explain 68% of property crime variation, and routine activity theory predicts over 70% of burglary patterns. The National Institute of Justice has funded 47 projects testing these models since 2015 - 83% confirmed their predictive power. However, they’re less accurate for intimate partner violence, where power dynamics matter more than routine.

Can these theories prevent cybercrime?

Yes - but only if updated. The original routine activity theory didn’t account for digital spaces. The 2023 "Routine Activity Theory 2.0" now includes online behavior. For example, posting vacation plans on social media creates a "suitable target" (empty home) and removes a "capable guardian" (no one watching). Reducing digital exposure - like turning off location tags - directly lowers cybercrime risk.

Do these theories work for everyone?

Not equally. Research shows they’re strongest for property crimes and street violence. They’re weaker for crimes driven by power and control, like sexual assault or stalking. That’s why modern victimology now combines lifestyle theory with structural analysis - looking at poverty, racism, and gender inequality. One-size-fits-all doesn’t work. Context matters.

What’s the biggest mistake people make with these ideas?

Thinking they’re about personal responsibility. They’re not. They’re about opportunity. A woman walking alone at night isn’t responsible for being attacked - but a poorly lit street is. The goal isn’t to change the victim. It’s to change the environment so crime doesn’t have a chance to happen.

What’s Next for Victimology?

The field is moving fast. By 2027, the National Institute of Justice plans to spend $12.5 million developing culturally specific risk tools for Indigenous communities - because blanket theories don’t work for everyone. Researchers are also testing how AI can analyze smartphone data to predict when someone is at risk - not to surveil, but to warn.

One thing’s clear: crime isn’t random. And prevention isn’t about punishment. It’s about understanding patterns - and changing the conditions that make crime possible.