When a photograph is presented in court, it doesn’t speak for itself. A picture might show a broken window, a bloodstain, or a suspect standing near a vehicle-but without a clear, accurate caption, it’s just an image. In legal proceedings, evidence photo captions are not just helpful notes. They’re legally required to prove what the photo actually shows. If the caption is vague, missing key details, or inaccurate, the entire photo can be thrown out-even if it’s the most compelling piece of evidence in the case.

Why Captions Matter More Than You Think

Courts don’t accept photos just because they look real. Under the Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE), Rule 1002, you need the original to prove the content. That means if you’re using a digital photo, you can’t just hand it to the judge and say, "This is what happened." You have to prove it’s genuine, unaltered, and properly connected to the facts of the case. That’s where the caption comes in. A caption isn’t just "Photo 1: Crime Scene." That’s not enough. Think about it: if you’re a juror, and you’re looking at a photo of a person holding a gun, but the caption doesn’t say when, where, or who took it, how do you know it’s not staged? How do you know it’s from the same night of the robbery, or even from the same city? The Advisory Committee Notes on FRE 901 make it clear: testimony from a witness who saw the scene is the most common way to authenticate a photo. But in real-world cases, that witness might be gone, unavailable, or not qualified to explain everything. That’s when the written caption becomes the backup-the written record that stands in when the witness can’t.What a Legally Sufficient Caption Must Include

Based on court rulings, federal guidelines, and law enforcement best practices, a photo caption that holds up in court needs six core elements:- Case number - So the photo can be tracked across reports, databases, and hearings.

- Date and time (to the minute) - Timestamps prevent claims that the photo was taken days later or manipulated after the fact.

- Precise location - Not just "near the store," but "northwest corner of 5th and Main, 15 feet from the entrance, GPS coordinates 45.5231° N, 122.6765° W."

- Photographer’s name and badge number - Accountability matters. If someone challenges the photo’s authenticity, you need to know who took it and whether they were trained.

- Subject description - "Man in red hoodie" is better than "person." "Black 2021 Ford F-150, license plate OR-789KLM" is better than "vehicle."

- Contextual narrative - Why is this photo important? "Photo shows blood trail leading from back door to vehicle, consistent with victim’s reported escape route."

The International Association for Identification (IAI) published these exact requirements in 2020, and most major law enforcement agencies now follow them. But even with these standards, mistakes still happen.

What Goes Wrong in Real Cases

A 2022 survey by the American Bar Association of over 1,200 attorneys found that 68% had faced a challenge to photographic evidence because of bad captions. Here’s what they saw most often:- Missing timestamps (47%) - Photos taken hours after the event, with no time stamp, were used to imply immediate aftermath. Judges ruled them inadmissible.

- Unclear subjects (39%) - A photo labeled "suspect" turned out to be a bystander. No name, no description, no identification. The defense won the challenge.

- Missing context (28%) - A photo of a knife on a table was labeled "weapon found at scene." But the caption didn’t say it was recovered from the suspect’s pocket, or that it was wiped clean. The defense argued it was planted. The photo was excluded.

One case from Maryland, Lorraine v. Markel American Insurance Co. (2007), set a major precedent. The court ruled that digital photos must be accompanied by testimony about how they were created, stored, and transferred. No metadata. No chain of custody. No caption. The evidence was tossed.

Even if the photo is real, if you can’t prove it hasn’t been changed, courts will assume the worst.

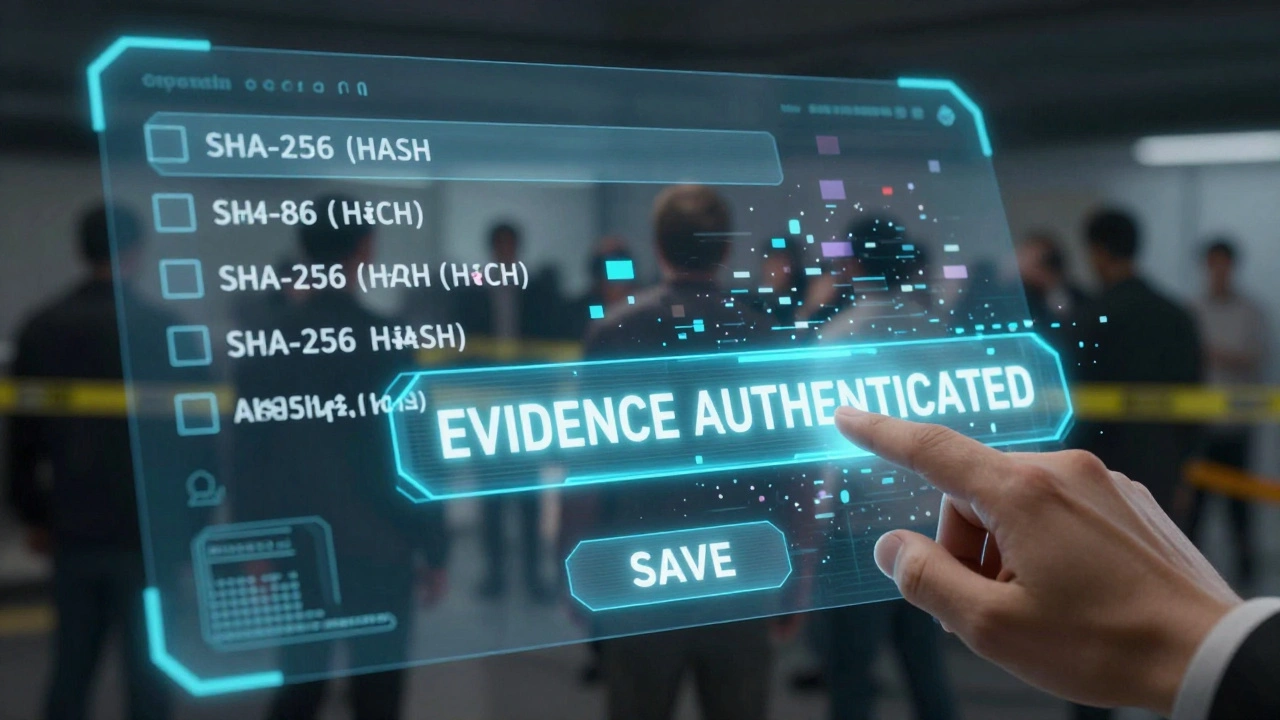

The Role of Metadata and Digital Integrity

Digital photos come with hidden data-EXIF metadata-that includes camera settings, GPS location, and timestamps. But that data can be stripped, edited, or altered. That’s why the Department of Justice’s Electronic Discovery Reference Model (EDRM) requires cryptographic hash verification (SHA-256) for digital evidence. A hash is like a fingerprint for a file. If the file changes-even by one pixel-the hash changes. If a photo’s hash matches the original stored in the evidence system, you’ve got proof it hasn’t been tampered with. But if the caption doesn’t reference the hash or the storage protocol, the defense can argue the photo was altered. NIST’s 2021 guidelines (NISTIR 8349) say photos should include ISO 15489-1:2016-compliant metadata fields. That means: creator, date/time, location, and purpose. If your agency uses software that doesn’t capture this, you’re already behind.How Technology Is Changing the Game

The market for digital evidence management software hit $2.4 billion in 2022. Why? Because agencies realized they couldn’t rely on handwritten labels or Excel spreadsheets anymore. Platforms like Axon Evidence, Picaria, and CaseFleet now have built-in templates that force users to fill in all required fields before saving a photo. The International Association of Chiefs of Police found that in 2018, only 57% of agencies used such systems. By 2022, that jumped to 83%. And guess what? The National Center for State Courts reported a 22% drop in evidence challenges tied to poor photo labeling. It’s not magic. It’s structure. When the system asks you for GPS coordinates, and you can’t skip it, you don’t forget.

What’s Coming Next: Deepfakes and AI

In May 2023, the Administrative Office of U.S. Courts announced it would form a committee to update evidence rules for AI-generated images. By mid-2025, draft guidelines are expected. Why? Because AI can now create hyper-realistic fake crime scene photos. A deepfake could show a suspect at a location they never visited. California already took action. As of January 1, 2024, Evidence Code Section 1510 requires explicit disclosure if a photo was enhanced, edited, or generated with AI. The caption must state: "This image was digitally altered using AI software on [date]." The Uniform Digital Evidence Act is being drafted by 17 states. It will standardize caption rules nationwide. No more confusion between counties. No more loopholes.What You Should Do Today

If you’re handling photographic evidence-whether you’re a cop, a forensic technician, or a legal assistant-here’s what you need to do right now:- Stop using generic labels like "Photo 1," "Crime Scene," or "Suspect."

- Use a standardized template that includes all six required elements.

- Ensure metadata is preserved and hashed (SHA-256) upon capture.

- Train everyone who handles photos: if they don’t know the caption rules, they’re risking the whole case.

- Review every photo before submission. Ask: "Would a defense attorney be able to challenge this?" If yes, fix it.

There’s no such thing as a "good enough" caption. In court, the difference between admissible and excluded evidence often comes down to a single missing timestamp or an unclear subject description.

Photos tell stories. But only if they’re properly labeled.

Can a photo be admitted into evidence without a caption?

Technically, yes-but only if a witness testifies live to authenticate it. The witness must describe what’s in the photo, when and where it was taken, and confirm it accurately represents the scene. Without that testimony or a written caption, the photo is vulnerable to exclusion under FRE 901. In practice, most courts require both.

What happens if the photo’s metadata is deleted?

Deleting metadata raises red flags. Courts treat it as a potential attempt to hide evidence tampering. If the original file is lost and only a copy remains without EXIF data, the burden shifts to the prosecution to prove authenticity through other means-like witness testimony or chain-of-custody logs. If those are weak, the photo will likely be excluded.

Are handwritten captions acceptable?

Handwritten captions on printed photos are acceptable if they contain all required details and are signed and dated by the photographer or evidence custodian. However, they’re harder to verify and more prone to errors. Digital captions with embedded metadata are strongly preferred and increasingly required by court standards.

Do private investigators need to follow the same rules?

Yes. Any photo submitted as evidence in a U.S. court, regardless of who took it, must meet FRE standards. Private investigators often face tougher scrutiny because their work isn’t governed by the same protocols as law enforcement. Without proper labeling, their photos are more likely to be challenged and excluded.

Can AI-generated images ever be used as evidence?

Only if they’re clearly disclosed as AI-generated and accompanied by full documentation of the source, algorithm used, and purpose. California’s 2024 law requires this. Courts in other states are likely to follow. A photo created by AI without disclosure will be automatically excluded as misleading.