What Protective Orders Really Do for Forensic Data

When a court case involves digital evidence-like medical records, phone logs, DNA profiles, or surveillance footage-there’s a real risk that sensitive information could leak. A protective order is a court-issued legal directive that limits who can see, copy, or share confidential forensic data during litigation. It’s not just a formality. It’s a shield. Without one, a victim’s private health history, a suspect’s encrypted communications, or a company’s proprietary forensic algorithms could end up on public court records, social media, or worse-on the dark web.

Why Most Protective Orders Fail

Many protective orders are written in vague language like "reasonable efforts" or "secure manner." That’s not enough. In Pfizer, Inc. v. Natco Pharma, Inc., the court pointed out that saying data must be stored "in a secure manner" is practically meaningless. It doesn’t say how secure, who can access it, or what happens if someone hacks it. That kind of language leaves gaps. Attackers don’t need to break into a courtroom-they just need to exploit a weak law firm’s unencrypted laptop or a vendor’s poorly secured cloud server.

Effective protective orders don’t just ask for good intentions. They demand specific actions. For example, they require:

- Encryption using AES-256 or equivalent for all digital files

- Access limited to only those with a court-approved need-to-know

- Physical documents stored in locked, access-controlled law office safes-not personal desks or home offices

- Electronic files only accessible through secure litigation portals with two-factor authentication

- Devices used to view data must be encrypted and wiped after the case ends

The Legal Foundation: Rule 26(c) and Beyond

The power to issue protective orders comes from Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26(c) which allows courts to issue orders to protect parties from "annoyance, embarrassment, oppression, or undue burden or expense". But this isn’t a blank check. Courts must balance transparency with privacy. The default rule is that court documents are public. To seal something, you have to prove the harm from disclosure outweighs the public interest in openness.

That’s why motions for protective orders must include a summary of the sensitive data-without revealing it. You can’t just say "this is private." You have to show why it’s private. A medical record showing a patient’s HIV status? That’s clear. A forensic report detailing how a smartphone was hacked? That might be trade secret material. Each needs a different justification.

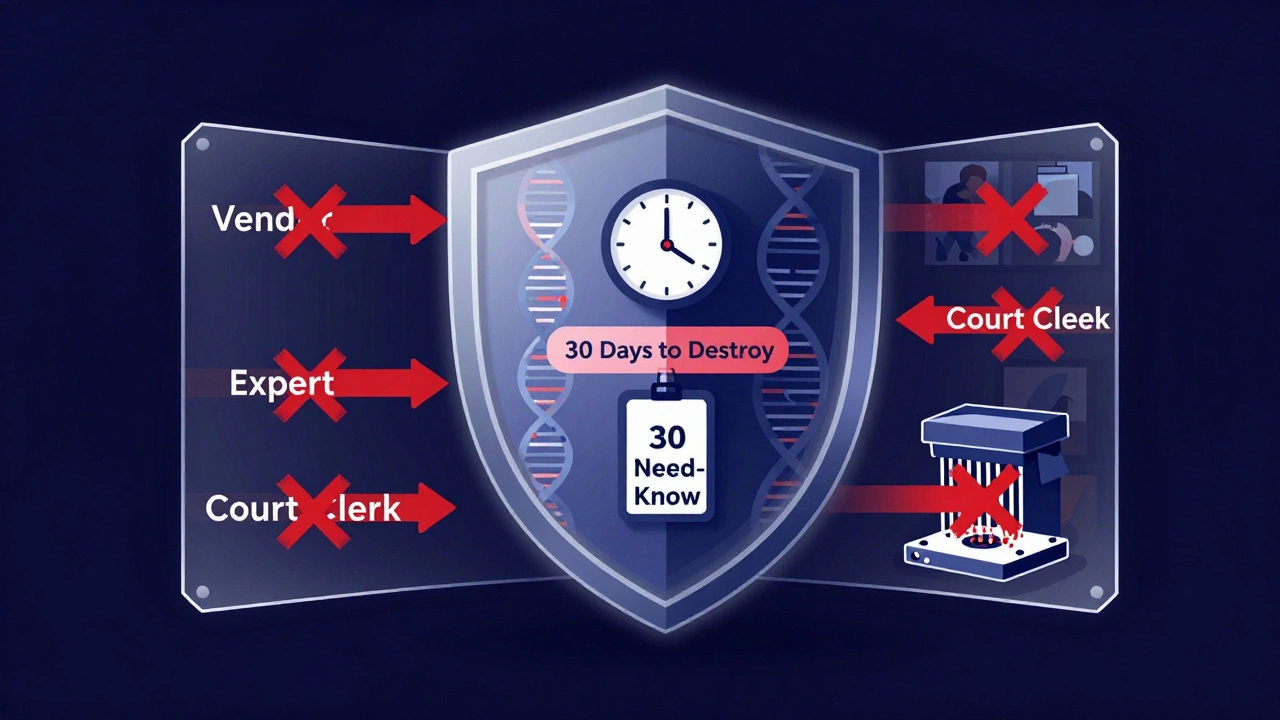

Who Gets Access-and Who Doesn’t

Protective orders aren’t just about lawyers and clients. They control access for everyone involved:

- Experts: Forensic analysts, cybersecurity consultants, and medical reviewers must sign agreements under the order.

- Vendors: eDiscovery firms, cloud storage providers, and transcription services are now explicitly covered. If they handle the data, they’re bound by the same rules.

- Court staff: Clerks and judges handling sealed documents must follow strict protocols to prevent accidental leaks.

- Third parties: If a witness’s phone is seized, the order must prevent the data from being shared with unrelated agencies or commercial entities.

One common mistake? Assuming a vendor’s "standard NDA" is enough. It’s not. A protective order overrides any private contract. It’s court-enforced. If a vendor violates it, they can be held in contempt-even if they didn’t sign anything directly.

Encryption, Retention, and Destruction Rules

Protective orders now specify how long data can be kept and how it must be destroyed. The Drug and Device Law Blog (June 2025) highlights that courts are increasingly requiring destruction within 30 days of case closure, unless otherwise ordered.

Here’s what a strong destruction clause looks like:

- All electronic copies must be permanently deleted from all devices and cloud backups

- Hard drives used to store data must be physically shredded or degaussed

- A sworn affidavit must be filed proving destruction was completed

Retention is just as important. Some orders require data to be preserved for the full statute of limitations-even after the case ends. Why? Because future lawsuits might arise from the same incident. A protective order can’t just be a "use it and toss it" system.

HIPAA and the Special Case of Medical Data

When forensic data includes health records, HIPAA Qualified Protective Orders (under 45 C.F.R. §164.512(e)(1)(ii)(B)) apply. These aren’t optional. Courts must follow federal healthcare privacy rules. A forensic report from a hospital’s electronic system? It’s protected under HIPAA even if it’s not a patient’s name-it could still be re-identified.

These orders require:

- Removal of all 18 HIPAA identifiers before sharing

- Limiting use to the litigation only-no research, no marketing, no training

- Prohibiting re-identification attempts

Violating a HIPAA protective order can trigger fines from the Department of Health and Human Services-even if the violator is a law firm, not a hospital.

What Happens When the Data Is Breached?

Protective orders now include breach protocols. The Pfizer v. Natco case set a clear standard: any breach must be reported within 72 hours.

That means:

- The party that lost the data must notify the opposing side immediately

- They must explain what was exposed, how it happened, and what steps they’re taking to fix it

- They must provide enough detail for the other side to assess risk-no vague "we’re investigating" statements

Failure to report within 72 hours? The court can impose sanctions, exclude evidence, or even dismiss claims. It’s not a warning. It’s a deadline.

Industry Standards Are Now the Minimum

Protective orders used to be written like contracts between lawyers. Now, they’re written like cybersecurity policies. Courts are starting to reference:

- NIST SP 800-171 for protecting controlled unclassified information

- ISO/IEC 27001 for information security management

- SOC 2 for service providers handling sensitive data

Logikcull’s 2023 analysis predicts that by 2028, 75% of federal courts will require protective orders to explicitly meet NIST 800-171 standards. That means encryption standards, access logs, audit trails, and vendor assessments will be mandatory-not optional.

The 5-Day Rule: Don’t Wait Too Long

Under 31 CFR § 501.733(c) , if a court requests more information about why data should be protected, you have five days to respond. Miss that deadline? You lose your claim to confidentiality. No exceptions. No extensions. This rule applies in federal administrative proceedings and is being adopted in more civil courts.

That means: if you’re filing for a protective order, don’t wait until the last minute. Gather your evidence, draft your motion, and file it early. Courts are tightening timelines because delays risk exposure.

What’s Next? The Future of Protective Orders

Protective orders are evolving from paper documents into automated systems. Some courts are testing integrated case management platforms that:

- Automatically apply access controls based on the order

- Block unauthorized downloads

- Log every view, print, or copy

- Send alerts if someone tries to export data

As forensic data becomes more digital-think AI-generated evidence, facial recognition logs, or neural data from brain scans-the need for precise, enforceable protective orders will only grow. The days of "we’ll handle it carefully" are over. Courts now expect technical rigor. If you’re handling forensic data in litigation, your protective order isn’t a formality. It’s your first line of defense.

Can a protective order stop evidence from being used in court?

No. A protective order doesn’t block evidence from being admitted. It only controls who can see it and how it’s handled. Evidence can still be presented in court-just under strict conditions. For example, a forensic report might be filed under seal, read aloud by a lawyer without showing the full document, or summarized to protect private details.

Do protective orders apply to state courts too?

Yes. While the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure set the baseline, every state has its own rules that mirror or expand on them. States like California, New York, and Washington have added specific protections for digital evidence and health data. Some states, like Mississippi, even limit how disclosed data can be used beyond the case.

What if a lawyer accidentally sends protected data to the wrong person?

It’s still a breach. Even if it was an accident, the protective order requires immediate reporting and remediation. The party who sent it must notify the other side within 72 hours, explain what happened, and take steps to recover the data. If the data was highly sensitive-like medical records or encryption keys-the court may impose penalties, including fines or exclusion of evidence.

Can a protective order be challenged?

Yes. Either side can file a motion to modify or lift the order. The court will review whether the original justification still holds. If new evidence shows the data isn’t truly sensitive, or if the public interest outweighs privacy concerns, the order can be changed or removed. But the burden is on the party challenging it to prove why.

Are there penalties for violating a protective order?

Yes. Violating a court-issued protective order is contempt of court. Penalties can include fines, sanctions, exclusion of evidence, or even dismissal of claims. In cases involving HIPAA or national security data, additional civil or criminal penalties may apply. Courts treat these violations seriously because they undermine trust in the legal system.