When a forensic scientist walks into a courtroom, they’re not just presenting data-they’re trying to answer a question that matters more than any lab result: Did this person do it? But here’s the problem. Most jurors, lawyers, and even judges don’t know what a DNA profile is, how a fingerprint is matched, or why a digital file can’t be trusted just because it’s on a hard drive. And when experts use jargon like probabilistic genotyping or morphological analysis, the room goes quiet. Not because the science is boring-but because no one understands it.

Forensics Isn’t Magic. It’s Math With a Story

Think of forensic science like weather forecasting. Meteorologists don’t say, "It’s definitely going to rain tomorrow." They say, "There’s a 70% chance of rain." Why? Because even the best models have limits. Forensic science works the same way. A DNA match isn’t a yes-or-no answer. It’s a probability. When a lab says "This DNA matches the suspect," what they really mean is: "If you picked a random person off the street, there’s a 1 in 1 billion chance they’d match this sample." That’s not certainty. It’s likelihood. The biggest mistake experts make? Saying "This is a match" without explaining what "match" actually means. Jurors hear "match" and think "proof." But science doesn’t work that way. Even fingerprint experts, who once claimed 100% individualization, now say: "The probability of two people having identical ridge patterns is so low it’s practically impossible." But "practically impossible" isn’t the same as "impossible." That tiny gap is where wrongful convictions creep in.The Three-Part Rule: What, How, But

The most effective forensic communicators use a simple three-part structure:- What - State the conclusion plainly. "The DNA from the crime scene matches the suspect’s profile."

- How - Explain the science in plain terms. "We looked at 20 specific spots on the DNA strand. Only about 1 in 1 billion unrelated people would share all 20."

- But - Acknowledge the limits. "This sample was exposed to rain for two days. That could have degraded part of the profile. We’re confident in the match, but we can’t rule out minor contamination."

Visuals Beat Words Every Time

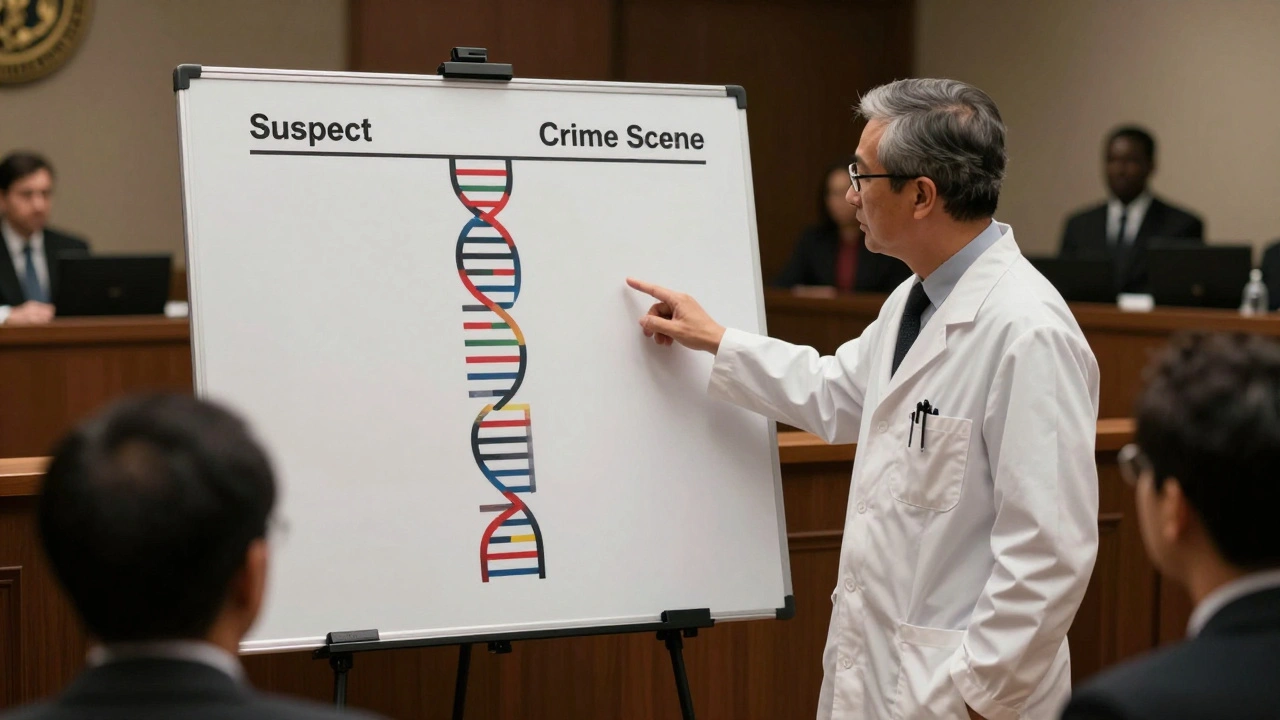

Try explaining a bloodstain pattern to someone who’s never seen one. You could say: "The spatter exhibits a high-velocity impact pattern consistent with a blunt force trauma." Or you could show a diagram with arrows, colors, and a scale-like a weather map of violence. The second version sticks. Forensic labs now use simple visuals because they work:- DNA matches? Show a ladder with 20 rungs. One side is the suspect. The other is the crime scene. Only one rung is missing. "That’s the part we couldn’t read because of moisture."

- Fingerprints? Compare them to puzzle pieces. "We don’t need the whole piece. We just need enough matching edges to say it’s the same puzzle."

- Digital evidence? Use a library analogy. "Finding this file on a hard drive is like finding one specific book in all the libraries in the world. We didn’t find it by accident. We found it because we knew exactly what to look for."

Why "Reasonable Scientific Certainty" Is a Trap

You’ve heard this phrase in court: "Based on reasonable scientific certainty..." It sounds authoritative. But here’s the truth: it’s meaningless. Jurors think "reasonable certainty" means "almost 100% sure." But scientists use it to mean: "We’ve done the tests. The data supports this conclusion. But we can’t eliminate every possible error." A 2023 survey of 500 attorneys by the American Bar Association found that 83% of defense lawyers wanted forensic reports to avoid phrases like "reasonable certainty" entirely. Instead, they wanted numbers: "There’s a 95% probability this fingerprint came from the suspect. There’s a 5% chance it didn’t." That’s why the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) now requires all forensic reports to include a "probability ladder" for DNA matches. Instead of saying "1 in 1 billion," they show a visual scale from "extremely unlikely" to "virtually certain." It’s not perfect-but it’s honest.The Danger of Over-Simplifying

Some experts try too hard to make things simple. They say: "This fingerprint is 100% from the suspect." That’s wrong. And dangerous. A 2023 study by the American Board of Criminalistics found that 63% of jurors believed fingerprint analysis gave absolute certainty. That’s not science. That’s TV. The truth? Fingerprint matching has a documented error rate. It’s low-about 1 in 1,000 cases-but it’s not zero. When experts say "100%," they’re not helping the case. They’re weakening it. The American Academy of Forensic Sciences now requires all experts to say: "No forensic method except DNA provides absolute certainty." That’s the new standard. And it’s working. Courts that enforced this rule saw a 29% drop in juror misunderstandings.

What Works in Court? Real Stories, Not Jargon

One forensic anthropologist at the Smithsonian explains bone trauma by saying: "Bones tell stories. This fracture? It’s like a diary entry. The angle tells us the weapon. The depth tells us the force. The healing tells us when it happened." Jurors nod. They get it. A digital forensic examiner in Texas says: "I don’t say ‘deleted files.’ I say: ‘Think of your phone like a notebook. When you rip out a page, it’s still there under the next page. I just look under the pages.’" That’s the kind of language that changes minds. The best forensic communicators don’t talk like scientists. They talk like storytellers. They use analogies from everyday life: puzzles, libraries, notebooks, weather forecasts. They don’t hide the uncertainty-they name it. And they show it.Training Isn’t Optional Anymore

Ten years ago, forensic scientists learned how to run a machine. Now, they have to learn how to explain it. Accredited forensic programs now require 120 hours of communication training-up from 45 hours in 2018. Entry-level analysts spend 6 to 9 months practicing testimony with mock juries before they ever step into a real courtroom. Why? Because when they do, lives are on the line. The FBI and Department of Justice now spend millions on communication training. Why? Because wrongful convictions tied to misunderstood evidence cost taxpayers millions-and destroy lives. States that required this training saw a 22% drop in evidence-related wrongful convictions over five years. It’s not about being flashy. It’s about being clear.What’s Next? The Future of Forensic Communication

New tools are coming. The Netherlands Forensic Institute launched a system called "Verbal Bridge" in early 2024. It scans technical reports and suggests plain-language replacements-94% accurate at keeping the science intact. AI won’t replace scientists. But it will help them speak better. By 2030, the goal is simple: 90% of jurors should understand the forensic evidence they hear. Not because it’s easy. But because justice depends on it. The science doesn’t change. But the way we talk about it? That has to.Why can’t forensic scientists just say "This is the suspect"?

Because science doesn’t work that way. A DNA match doesn’t mean the suspect was at the scene. It just means their DNA was found there. That could happen if they were there earlier, if someone else transferred it, or if there was contamination. Saying "This is the suspect" ignores context. Good communication says: "This DNA matches. Here’s how we know. Here’s what we can’t rule out."

What’s the biggest mistake forensic experts make when talking to jurors?

Using absolute language. Phrases like "100% certain," "no doubt," or "definitive match" are scientifically false and legally risky. Jurors hear them as proof. Experts mean "very strong evidence." But the difference between "very strong" and "absolute" is the difference between justice and a wrongful conviction.

How do jurors misunderstand DNA evidence?

They think a match means the suspect committed the crime. But DNA can be transferred. A person can leave DNA at a crime scene without being involved in the crime-by touching a doorknob, shaking hands, or even being in the same room. A match tells you the person’s DNA was there. It doesn’t tell you why. That’s why context matters more than the number.

Is it okay to use analogies like "finding a needle in a haystack"?

Yes-if they’re accurate. "Finding a needle in a haystack" is misleading because it implies randomness. DNA matching isn’t random. It’s targeted. A better analogy is "finding one specific book in every library in the world." That matches how forensic labs work: they’re not guessing. They’re looking for a precise match. The key is to pick analogies that reflect the actual process, not just make it sound dramatic.

Why do prosecutors want simpler language, but defense attorneys want more detail?

Prosecutors want convictions. They think clear, confident language helps. Defense attorneys want to protect the accused. They know that uncertainty is the foundation of reasonable doubt. The truth? Both sides need honesty. The best forensic reports give prosecutors their conclusion and defense attorneys their room to question. That’s why including uncertainty isn’t weakness-it’s fairness.