When documenting a crime scene, the first photograph you take can make or break a case. It’s not just about capturing what’s there - it’s about proving beyond doubt that what you captured was never altered, hidden, or manipulated before anyone else saw it. That’s why photography before evidence markers isn’t just a best practice - it’s a legal requirement in nearly every modern forensic system.

Why the Order Matters

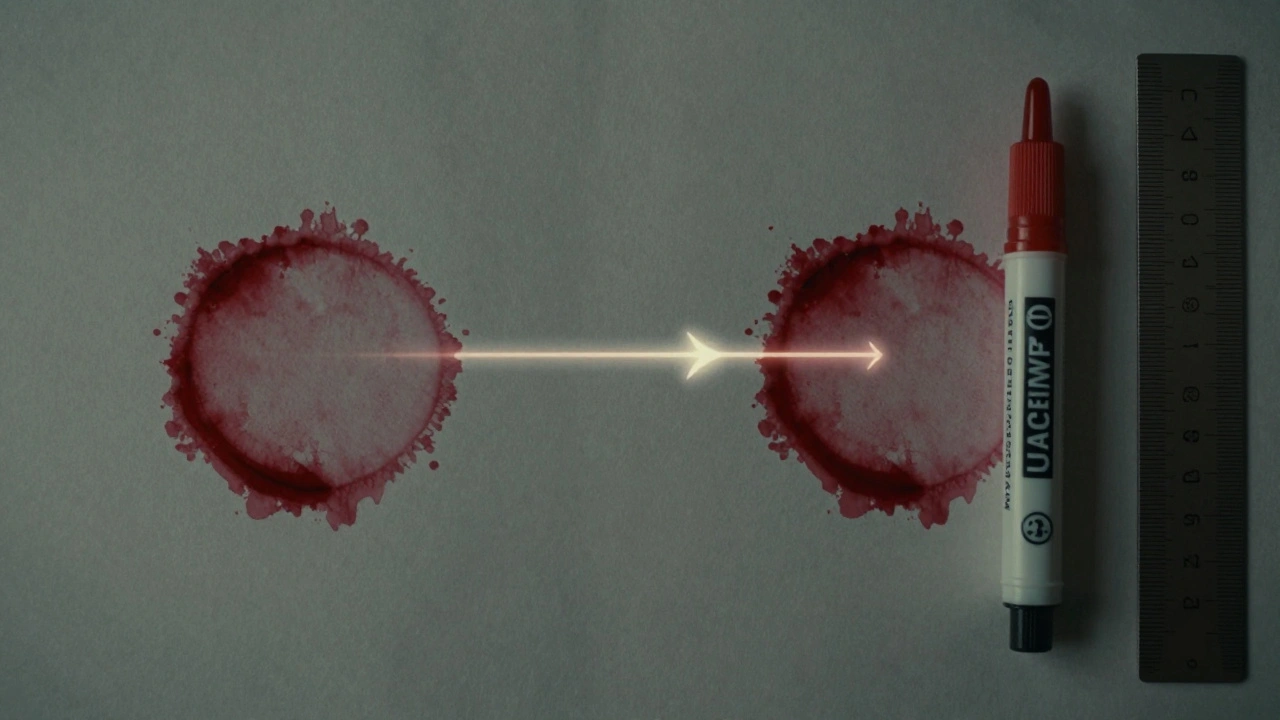

Picture this: You arrive at a homicide scene. A bloodstain spreads across the floor near a broken lamp. You grab your camera, step in, place a ruler and a numbered evidence marker right next to it, and snap a photo. Sounds logical, right? Wrong. That single action could cost you the case. The moment you put a marker down, you’ve changed the scene. Even slightly. Maybe the marker pressed into the blood, altering the pattern. Maybe it blocked a tiny fragment of glass or fiber underneath. Maybe it cast a shadow that hides a critical detail. The defense doesn’t need to prove tampering - they just need to create doubt. And if your first photo includes a marker, they’ve got their opening. The correct sequence is simple: Take the photo before you place anything. No markers. No rulers. No labels. Just the evidence, exactly as it was found. Then - and only then - do you introduce the scale and marker, and take a second photo. This creates a visual chain of custody that says: "This is what we found. This is what we added. Nothing was hidden. Nothing was moved."The Legal Backbone

This isn’t some departmental whim. It’s written into standards that govern how evidence is admitted in court. The FBI’s Crime Scene Investigator Handbook (2023) requires this sequence to be completed within 30 minutes of securing the scene. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication 1281 (2021) calls it "essential for evidentiary integrity." The 2022 PHR Guidelines for Forensic Photography go further, mandating that every image must be timestamped, geolocated, and stored in RAW format at a minimum of 24 megapixels. Why such strict rules? Because courts don’t trust assumptions. A 2023 study in the Journal of Forensic Sciences analyzed 1,247 cases. Photos taken before marker placement were admitted as evidence in 98.7% of trials. Photos taken after? Only 63.2%. That’s not a small gap - that’s a chasm. One missing photo can mean a conviction is overturned.How It’s Done Right

It’s not just about snapping two pictures. There’s a method.- Step 1: Wide-angle overview. Capture the entire scene from multiple angles. Show where the evidence sits in relation to walls, doors, furniture. This establishes context before anything is touched.

- Step 2: Mid-range shot. Zoom in slightly. Show the evidence and its immediate surroundings - no markers yet.

- Step 3: Close-up without scale. This is the critical one. Fill the frame with the evidence. No ruler. No number. Just the object as it lies. This photo proves nothing was obscured.

- Step 4: Close-up with scale and marker. Now place the ruler and evidence marker. Take the second photo. The marker should be placed so it doesn’t cover any part of the evidence.

Technical Details That Make or Break It

This isn’t a point-and-shoot job. Lighting, exposure, and camera settings matter.- ISO settings: Keep between 100-400. Too high, and you get noise that obscures fine details. Too low, and you risk motion blur.

- Aperture: f/8 to f/11. This gives enough depth of field to keep the entire evidence item sharp, even if it’s slightly uneven.

- Lighting: Use natural light if possible. If not, use forensic alternate light sources at a 45-degree angle. Direct overhead lighting creates shadows that hide textures. Side lighting reveals ridges, fibers, and stains.

- File format: Always shoot RAW. JPEGs compress data and lose detail. In court, the defense will demand the original file. If you only have a JPEG, you’ve lost.

- File naming: Use codes, not names. "PHR-22-001-01" means Phase 1, Item 1, Sequence 1. Never use "bloodstain_001.jpg" - that invites tampering claims.

Where It Breaks Down

Even the best protocols have flaws. In low-light environments - alleyways, basements, nighttime scenes - the marker-free photo can be too dark to be useful. A 2022 National Institute of Justice report found that 17.3% of nighttime crime scene photos lacked sufficient detail for analysis. Some departments now use long-exposure techniques or portable forensic lighting rigs to compensate. Digital evidence is another problem. If you’re photographing a phone screen, you can’t take a "marker-free" shot after turning it on. Once you power it on, you’ve altered the data. There’s no "before" to capture. That’s why many agencies now require screen captures to be taken before any physical interaction - and then documented with a photo of the device itself, without markers, before any labels are added. Then there’s time pressure. At complex scenes - multiple victims, scattered evidence, large areas - the 30-minute window feels impossible. One officer on Reddit’s r/Forensic wrote: "I had a murder case thrown out in 2021 because I placed the marker before the initial shot. The defense proved we could have hidden a bullet fragment under it."What Experts Say

Dr. John Pieters, former Chair of the IAI’s Photography Committee, put it bluntly: "The marker-free photograph provides the only verifiable record of what existed beneath the scale, preventing defense challenges regarding potential evidence tampering." But it’s not perfect. Retired LAPD photographer Mark Johnson noted in a 2022 interview that rigid adherence sometimes delays critical evidence collection. He recalled 14 cases where bloodstain patterns degraded before they could be documented because officers waited too long to get the "perfect" photo. Still, the data doesn’t lie. The 2023 NIST Forensic Science Standards Board rated this protocol as "Critical" - their highest level. And 92% of evidence exclusions in 2022 were tied to improper sequencing.

Training and Compliance

You can’t just wing this. The Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers require 45-90 minutes of specialized training. The International Association for Identification’s 40-hour Forensic Photography course includes 8 hours on this exact sequence. Novice photographers need 12-15 supervised scenes before they’re trusted to work alone. And compliance isn’t optional. ISO/IEC 17025:2017 - the global standard for forensic lab accreditation - now requires this protocol. In 43 U.S. states, failure to follow it results in automatic exclusion of evidence. The 2023 National Conference of State Legislatures confirmed that.The Future: Beyond the Marker

The future of forensic photography isn’t just two photos - it’s hundreds. The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department is piloting 3D scanning systems that create a full digital twin of the scene before any physical markers are placed. Their 2023-2024 trial showed 94.7% accuracy in reconstructing evidence positions. But here’s the catch: 12.3% of agencies still can’t store the dual-image sets required for the 7-year evidence retention period. That’s a growing problem. Digital storage costs money. Training costs money. And not every department has the budget. Still, the trend is clear. Marker-free photography isn’t going away. If anything, it’s becoming more rigid. The American Board of Criminalistics announced in January 2025 that certification exams will now include 15% more questions on documentation sequencing. And by 2030, the International Forensic Photography Association predicts a 20% drop in physical markers - replaced by augmented reality overlays projected directly onto digital reconstructions.Final Rule

There’s one rule that never changes: Photography before evidence markers. Always. No exceptions. No shortcuts. No "I’ll just do it this once." Because in forensics, the first photo isn’t just documentation. It’s your first line of defense - against doubt, against lies, against a case falling apart.If you skip it, you’re not just cutting corners. You’re putting justice at risk.