When evidence moves across state lines, county borders, or federal agencies, the simple act of handing off a blood vial or a hard drive can unravel an entire case. It doesn’t take a major mistake-just a missed signature, a delayed log entry, or an unsecured transfer-to make that evidence inadmissible in court. In multi-jurisdiction cases, where evidence travels through half a dozen different agencies before reaching a judge, the chain of custody isn’t just paperwork. It’s the thin line between justice and a guilty person walking free.

What Is Chain of Custody, Really?

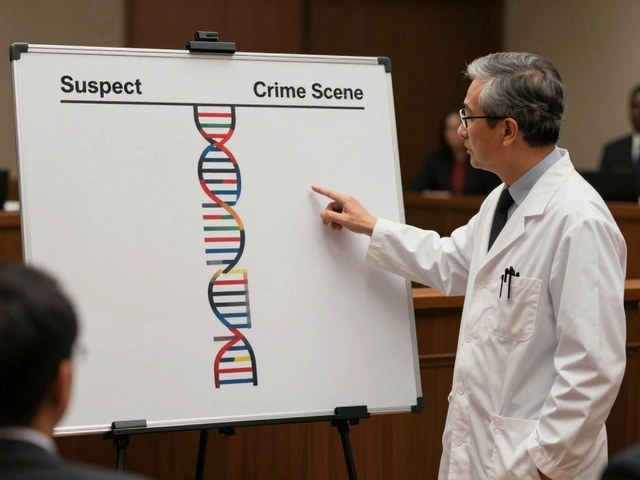

Chain of custody is the paper trail that proves evidence hasn’t been tampered with, lost, or switched. It’s not just a list of names. It’s a timestamped record of every person who touched the evidence, every place it was stored, every transfer made, and every security measure used. If you collect a DNA sample from a crime scene in Oregon and send it to a lab in California, then to a federal forensic center in Virginia, each handoff must be documented. One missing signature, one unlogged hour, and the defense can argue the evidence is contaminated-or worse, planted.

Under the Federal Rules of Evidence Rule 901, prosecutors must prove the evidence is authentic and unchanged. If they can’t, the judge throws it out. No second chances. No do-overs. That’s why a broken chain of custody isn’t just a paperwork error-it’s a case killer.

Why Multi-Jurisdiction Cases Are a Nightmare

Single-jurisdiction cases are hard enough. Imagine a local police department collects a gun, sends it to their own lab, and brings it to court. Everyone uses the same forms, same software, same training. Now multiply that by five. Ten. Twenty.

In multi-jurisdiction cases, evidence might pass through:

- Local sheriff’s office

- State police forensics unit

- Federal DEA or FBI lab

- County prosecutor’s evidence room

- State court clerk’s secure storage

Each one has different rules. One uses barcodes. Another uses RFID tags. One logs transfers in a digital system. Another still uses handwritten notebooks. Some labs require two signatures. Others? Just one. And no one checks if the others are even following the same standards.

This isn’t hypothetical. In 2024, a federal drug trafficking case in the Pacific Northwest collapsed because a blood sample sat in a locked trunk for 18 hours while being transferred between Oregon and Washington agencies. No log entry. No temperature record. The defense didn’t even need to prove tampering-just that the chain was broken. The judge excluded the evidence. The defendant walked.

The Human Factor: Where Chains Break

Technology can help. But people? They’re the weak link.

Think about it: in a major multi-jurisdiction case, dozens of people handle evidence. A patrol officer collects it. A detective transports it. A lab tech opens it. A prosecutor reviews it. A court clerk stores it. Each one has a different job, different training, different priorities.

One officer might think, “I’ll log it later.” Another forgets to seal the envelope with tamper-evident tape. A lab assistant grabs the wrong case number. A clerk misfiles a digital file. All of these seem small. But in court, the defense doesn’t care about your intent. They only care about the record.

And they’re trained to find these gaps. Defense attorneys don’t wait for mistakes. They hunt them. They subpoena every log, every camera feed, every transfer receipt. They look for gaps in time. Missing initials. Handwritten notes that don’t match digital entries. If there’s a single inconsistency, they’ll argue the whole chain is unreliable.

Digital Evidence Makes It Worse

Physical evidence is bad enough. Digital evidence? It’s a minefield.

A suspect’s phone might be seized in California, analyzed in Texas, and backed up in Georgia. Each agency uses different tools. One uses Cellebrite. Another uses Forensic Toolkit. One makes a bit-for-bit clone. Another just copies files. One encrypts the drive. Another leaves it on an unsecured USB.

And here’s the kicker: just opening a file can change metadata. Opening a folder on a seized hard drive might update the “last accessed” timestamp. That’s not tampering-but the defense will say it is. If the original forensic image isn’t properly documented, the defense can argue the data was altered before it was even analyzed.

Without a clear, unbroken audit trail, digital evidence is often tossed out-even if it’s the only proof of guilt. In 2023, a child exploitation case in the Midwest was dismissed because the FBI’s forensic report didn’t match the timestamp on the evidence drive. The defense proved the drive had been connected to an internet-connected computer before analysis. The court ruled: no chain of custody. No case.

Storage and Transfer Risks

Where evidence is stored matters just as much as who handles it.

Some jurisdictions have climate-controlled, biometric-locked evidence rooms. Others? A locked closet in a back room. One agency might use blockchain-backed digital logs. Another still uses Excel spreadsheets printed on paper.

Transfers are especially dangerous. If evidence is moved by courier, who signs for it? If it’s flown between agencies, was it in a secure container? Was the temperature monitored? Was the transfer logged within 24 hours? If not, the defense will argue the evidence could have been switched during that gap.

And don’t forget: if evidence is lost-even temporarily-it’s often automatically excluded. No one gets to say, “Oh, we found it later.” The damage is done. The chain is broken.

What Fixes This?

There’s no magic bullet. But there are proven solutions.

- Centralized digital evidence management systems-platforms that track every item with barcode or RFID, auto-log transfers, and require digital signatures. These systems create immutable records that can’t be altered after the fact.

- Standardized protocols-agencies across jurisdictions need to agree on one set of rules. Not “best practices.” One rule. One form. One system. Even if it’s not perfect, consistency beats chaos.

- Joint training-officers from different agencies should train together. Not just once. Regularly. When a state cop knows what a federal agent’s process is, they’re less likely to mess it up.

- Blockchain for audit trails-while not foolproof, blockchain-based logs provide tamper-proof timestamps. If evidence is moved, the system records the exact time, who did it, and where it went. No backdating. No editing.

- Independent audits-outside auditors should randomly check evidence storage and transfer logs. Not just once a year. Quarterly. Surprise inspections keep people honest.

The best systems don’t just track evidence-they protect the integrity of the entire process. And they don’t rely on people remembering to log things. They make logging automatic.

The Cost of Failure

When a chain of custody breaks, it’s not just one case that’s lost. It’s trust in the system.

Guilty people walk. Victims don’t get closure. Prosecutors spend months rebuilding cases. Courts get clogged with retrials. Taxpayers foot the bill. And the public starts to wonder: if the system can’t even keep track of evidence, how can we trust it to deliver justice?

It’s not about perfection. It’s about accountability. If every agency involved in a multi-jurisdiction case used the same digital system, followed the same protocol, and trained their staff the same way, these failures would drop by 80%. That’s not speculation. That’s what the National Institute of Justice found in its 2025 review of 1,200 multi-jurisdiction cases.

What’s holding us back? Not technology. Not money. It’s inertia. Agencies don’t want to change. They don’t want to share. They don’t want to be accountable to someone else’s rules.

But if we keep doing things the old way, more cases will keep falling apart. And the people who need justice the most? They’ll be the ones left behind.

What happens if the chain of custody is broken?

If the chain of custody is broken, the evidence can be ruled inadmissible in court. Prosecutors must prove the evidence hasn’t been altered or contaminated. If they can’t, the judge will exclude it-no matter how critical it is to the case. This can lead to dismissed charges, reduced sentences, or acquittals, even when guilt is clear.

Can a defense attorney challenge chain of custody even if no tampering occurred?

Yes. Defense attorneys don’t need proof of tampering. They only need to show a gap in the documentation-a missing signature, an unlogged transfer, a delay in processing. Any inconsistency can be used to argue the evidence isn’t reliable. The burden is on the prosecution to prove the chain was never broken.

Why is digital evidence harder to track than physical evidence?

Digital evidence can be altered without leaving physical traces. Opening a file changes metadata. Copying data can overwrite timestamps. If the original forensic image isn’t properly secured or logged, the defense can claim the data was modified. Unlike a blood vial, you can’t see if a hard drive was tampered with-only if the audit trail proves it wasn’t.

Do all law enforcement agencies follow the same chain of custody rules?

No. Each jurisdiction-local, state, federal-often has its own policies. Some use digital tracking systems. Others still use paper logs. This inconsistency is one of the biggest reasons chains break in multi-jurisdiction cases. Without standardized protocols, errors are inevitable.

What technologies help improve chain of custody?

RFID tags, barcode scanning, blockchain-based audit logs, and centralized digital evidence management systems all help. These tools automatically record who handled evidence, when, and where. They reduce human error and create tamper-proof records that courts can trust. Agencies using these systems report 70% fewer chain-of-custody challenges in court.