Most people think fingerprints are set at birth - but they’re actually formed long before a baby takes its first breath. By the time a child is born, their fingerprints are already permanent. Yet, trying to use them for identification? That’s where things get messy. Parents, daycare workers, and even law enforcement officers have all run into the same problem: children’s fingerprints don’t work like adults’ - not even close.

How Fingerprints Form Before Birth

Fingerprint development starts around week 10 of pregnancy. Tiny bumps on the fetus’s fingers begin to press against the amniotic sac, and that’s the first trigger. As the skin grows faster in some areas than others, it buckles and folds. These folds become ridges - the same ridges that will last a lifetime. By week 17 to 21, the pattern is locked in: loops, whorls, arches - all unique. Even identical twins, who share the same DNA, end up with completely different prints. That’s because fingerprints aren’t coded in genes. They’re shaped by pressure, movement, and the exact conditions inside the womb - how much amniotic fluid surrounds the fingers, how often the fetus touches its own face or the uterine wall, even the angle of the hand at a given moment.This isn’t just biology - it’s physics. The ridges form due to stress in the basal layer of the skin, not because of surface curvature. That means it’s not about how the skin looks on the outside - it’s about how the layers underneath are pushing and pulling against each other. Once the keratin layer forms around week 19, the ridges harden into their final shape. After that, nothing changes in the pattern. Not growth. Not injury. Not time. The ridges stretch as the child grows, but the overall design stays the same.

Why You Can’t Just Scan a Newborn’s Finger

If you’ve ever tried to get a fingerprint from a baby under six months old, you know how frustrating it is. The scanner beeps. The screen says “poor quality.” You try again. And again. And again. It’s not you - it’s the baby’s skin.Infant fingerprints have lower contrast, softer ridges, and more distortion than adult prints. NIST data shows adult fingerprint ridge spacing averages 8-9 pixels wide. For babies under six months? It’s 5-6 pixels. That’s too fine for most scanners to catch clearly. Their skin is also more elastic, more moist, and less rigid. A scanner designed for adults sees a smudge, not a pattern.

Studies show that biometric systems have only a 38.7% success rate with children under two years old. At six months? It’s worse. Over 80% of prints from infants in this age group are rated “level 5” - the worst possible quality by NIST standards. That’s why daycare centers using fingerprint check-ins often end up letting parents sign in manually. One parent on Reddit said they tried 15 times before the system finally accepted their 8-month-old’s print. The staff just shrugged: “It’s normal. Wait until they’re two.”

When Do Children’s Fingerprints Become Reliable?

It’s not a magic age - it’s a process. Around 6 to 9 months, ridges start to become more defined. By 12 months, the contrast improves enough that some scanners can work - but only if they’re designed for kids. By 18 months, success rates climb to about 75%. At age two? That jumps to 90%. That’s why experts recommend waiting until a child is at least 18-24 months old before relying on fingerprint identification for anything important.There’s also a big difference between getting a print and using it reliably. A 2022 study found that using more than one finger - say, both index fingers - increased accuracy for children under two by nearly 40%. That’s why some schools and hospitals now enroll multiple fingers for kids. It’s not just backup - it’s necessity.

And it’s not just about technology. Technique matters. Warming the child’s hands helps. Gentle pressure, not pressing hard. Multiple attempts from different angles. The International Association for Identification says proper child fingerprinting requires patience, not power. Most commercial baby fingerprint kits? They’re useless. They don’t explain this. They just show a pretty box with a little ink pad. Parents try once, get a blurry smudge, and give up. By 14 months, one mom on BabyCenter finally got a usable impression - after three failed attempts.

How Fingerprints Grow - And What That Means for Recognition

Fingerprints don’t just sit still. As the child grows, the ridges stretch. Between ages six and 16, the distance between ridge features grows at about half the rate of overall height increase. That means a fingerprint taken at age 3 won’t match exactly to one taken at age 12 - even though it’s the same person. This is why adult biometric systems fail so badly with kids. They’re not designed to account for growth.That’s changing. In January 2024, NIST released a new standard for children’s fingerprint quality - one that actually measures prints based on age. And in February 2024, NEC Corporation rolled out ChildMatch 4.0, a new algorithm that claims 94.7% accuracy for kids aged 12 to 24 months. That’s a 28% improvement over their old system. It works by predicting how the print will grow and adjusting the match accordingly. Think of it like stretching a photo to fit a bigger frame - but with math, not pixels.

Future systems are even smarter. MIT is testing temporary tattoo-like patches that enhance ridge visibility in infants. Google has filed a patent for AI that can reconstruct blurry prints by learning from thousands of child fingerprints. And Fujitsu is testing palm vein scanning alongside fingerprints - because sometimes, the palm is easier to read than the finger.

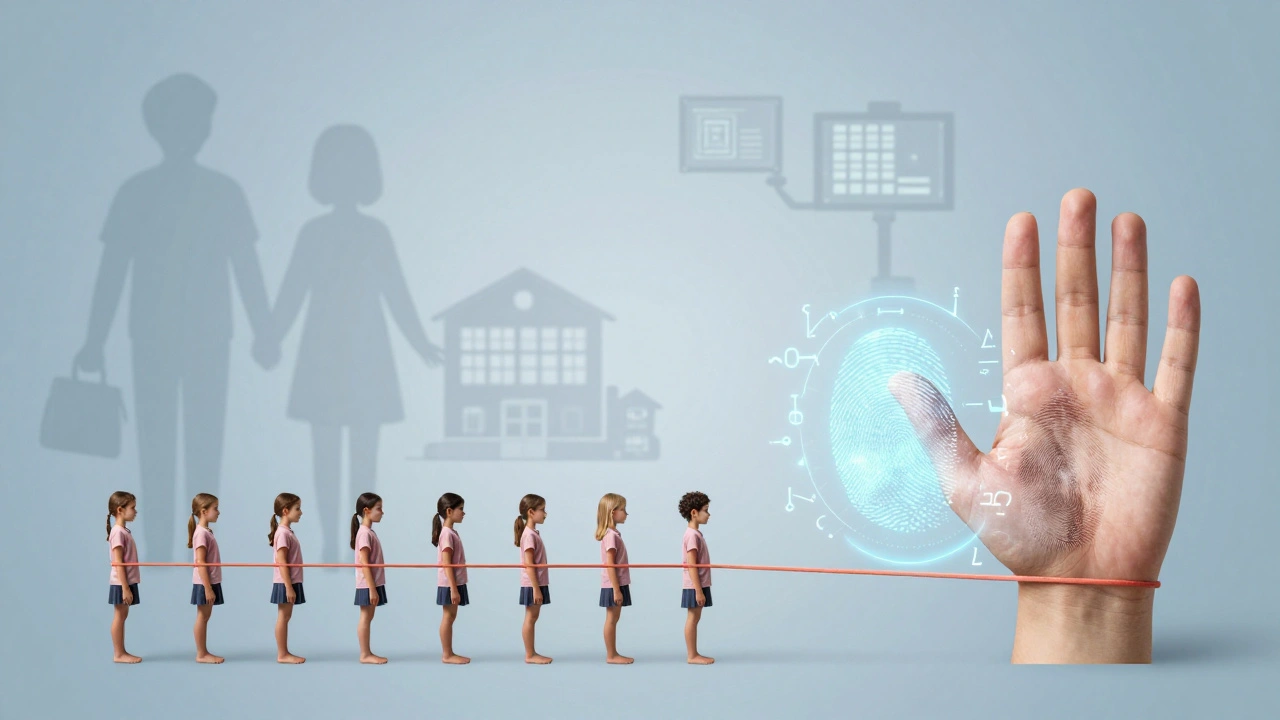

Why Governments Use Them - And Why Parents Worry

Despite the challenges, governments are pushing forward. In 2023, 78 out of 195 UN member countries started using child fingerprints - mostly for border control, school ID systems, and medical records. The global market for children’s biometrics hit $2.37 billion last year. NEC, 3M, and IDEMIA are fighting for dominance. But it’s not without pushback.The European Union’s GDPR treats children’s biometric data as “special category” information. That means collecting it requires explicit parental consent, strict limits on storage, and no use for non-essential purposes. In the U.S., the ACLU filed 17 lawsuits in 2023 against schools that fingerprinted kids under 13, arguing it violated the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA). A 2023 Pew Research survey found 63% of U.S. parents had “significant concern” about storing their child’s fingerprint data.

And here’s the real question: if a child’s fingerprint is permanent, and it’s collected before they can understand consent - who owns it? Who controls it? What happens when they turn 18? There are no clear answers. Ethicists warn we’re building a biometric identity for children before they’ve even learned to say their own name.

What This Means for Parents and Professionals

If you’re a parent trying to get your child’s prints for jewelry or a keepsake: wait until they’re at least 12 months old. Use professional ink pads, not cheap kits. Clean their hands, warm them gently, and try multiple fingers. You’ll have better luck.If you’re a school, daycare, or hospital worker: don’t use adult scanners on kids. Invest in 1000 dpi resolution devices. Train staff on gentle technique. Always allow alternative ID methods - photo, name, parent verification. Don’t assume a failed scan is a user error.

If you’re in law enforcement or forensics: don’t rely on fingerprints from children under three. Use footprints, dental records, or DNA instead. The data is there - it’s just not reliable in a fingerprint database designed for adults.

Children’s fingerprints are fascinating. They’re formed in the womb, shaped by chance, and last forever. But they’re not ready for prime time until the child is old enough to hold still - and the technology is old enough to understand them.

Can a baby’s fingerprint be used for identification right after birth?

No. A newborn’s fingerprints are too faint, too soft, and too small for most scanners. Ridge detail doesn’t become clear enough for reliable identification until around 6-9 months of age. Even then, success rates are low. Most systems require the child to be at least 12-18 months old before they work consistently.

Why do identical twins have different fingerprints?

Identical twins share the same DNA, but fingerprints aren’t genetically determined. They form based on physical pressures in the womb - how the fetus moves, where fingers touch the amniotic sac, and how skin layers buckle under stress. Even tiny differences in position or fluid pressure lead to unique ridge patterns. That’s why no two people, even identical twins, have the same fingerprints.

What age is best to get a child’s fingerprint for keepsakes?

The best time is between 12 and 24 months. By then, the ridges are more defined, the skin is less oily, and the child is more likely to stay still. Many parents try earlier and get smudged prints - waiting a few months makes a huge difference in quality. Always use professional kits with non-toxic ink and proper pressure guidance.

Can children’s fingerprints be altered or erased?

No. Once formed by week 24 of gestation, fingerprint patterns are permanent. Even deep cuts, burns, or scars won’t erase the underlying ridge structure - they may distort it temporarily, but the original pattern reappears as the skin heals. This permanence is why fingerprints are used for identification - but it also raises ethical concerns when collected from children.

Are there special scanners for children’s fingerprints?

Yes. Standard adult scanners use 500 dpi resolution. For children under two, experts recommend 1000 dpi scanners with higher sensitivity. These devices can capture finer ridge details and handle softer, more elastic skin. Some government and school systems now use these specialized scanners - but most consumer and commercial products still don’t.